IV

When Lillias Smith married William Smith in 1856, she broke the weaving tradition of her family and was set free from the factory work of a powerloom weaver. William's family had also been in Glasgow for generations, but this family of Smiths did not follow an unbroken family craft. William's Grandfather, also a William, married Jean Galbreath in 1795. At the time of the marriage, William was a skinner in Calton, a weavers village on the eastern edge of Glasgow. This was during the period when handloom weavers were able to command good earnings from their craft. So it is that by the birth of their second child, William was listed as a weaver. As mentioned above, the prosperity of the weavers trade did not last, and the craft was not passed on to the next generation of this family of Smiths. When William's

son (also William) married Helen Lillie in 1831 the marriage record showed him to be a carter. In this branch of the family, there had not been a long history in the handloom industry, and they did not have the economic base of Lillias' family to endure in the changing market. On the other hand, they adapted quickly, and as a result, attained an enviable position in Glasgow's process of industrialization.

Industrialization led immediately to the growth of the transport industry. Large, centralized manufacturing required quick, dependable transport for goods and raw materials. Early carriers like Wordie and Company were inconsistent until the 1820s and 1830s, when the changing economy led to a new outburst of activity. It was in this time period that William Smith became a carter. His father-in-law, Adam Lillie, was a labourer in Glasgow, and historical records show that the local depots of Wordie and Company regularly employed carters and labourers. It may be that this growth industry of the first half of the nineteenth century brought the Smiths and the Lillies together.

A great event in the evolution of the transport industry was the opening of the Garnkirk and Glasgow Railway in 1831. William Wordie soon realized that the railways could provide great opportunities for carriers. He was able to develop his carrier service at a time when people were still guessing as to the role that the railways might play. At that time, the concept of the railway was so new, no one knew what might become of it. Many thought of the rails as they did the canal system or toll roads. A common belief was that companies would pay a use fee to run their privately owned trains on the track owned by a separate authority. It did not take long to realize that this would create impossible operational difficulties.

Wordie realized that the inflexibility of the rail routes were the key to the success of his cartage business. Coal would have to be hauled to the railheads, and goods and merchandise between the train and the factory. It was in the connection between the factory and the railway that William Wordie saw his opportunity. In succeeding years, he made contracts with specific railways for cartage, among them was the Caledonian Railway, one of the more aggressive systems in an expanding industry.

It is quite possible that William Smith was a carter for a firm such as Wordie and Company. For in Scotland, employers relied on a patronage system. Long-term employees could secure jobs for their sons, and the reputation of the father would benefit the placement of the son. The work history of William Smith was that he began his married life as a carter. By the time his son, William, married in 1856, he was a coal agent and his son was a stoker for the Caledonian Railway. The connection with the Caledonian Railway implies that Wordie and Company was the

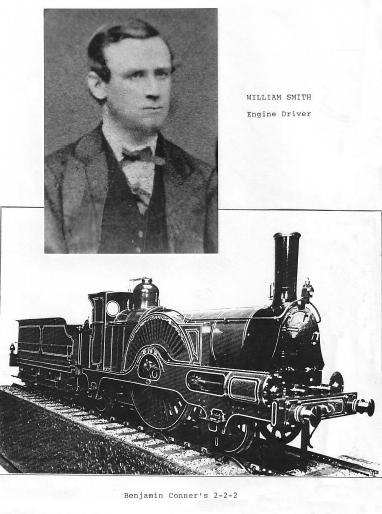

original carrier that employed William Smith. The fact that the son became a stoker for the Caledonias was a tribute to the father. By modern standards, being a stoker may not seem a high calling, but in the 1850's, it was a ticket to glamour and success. Being a stoker was the entry point, and twenty year old William Smith knew that all engine drivers began their railway careers as stokers. Indeed, William Smith realized the dream of many young men in the age of steam when he became an engine driver for the Caledonian Railway. While my American great-great grandfather, Jacob Ruth, was on the battlefield at Gettysburg, my Scottish great grandfather, William Smith was driving a Conner

2-2-2 locomotive on the main route between Glasgow and Carlisle.

When first married, William and Lillias Smith lived on Stirling Road in Glasgow's central district. This would have located them near the Buchanan Street station which was opened by the Caledonian in 1849. By this time, Glasgow was suffering from uncontrolled growth, and with the urban problems that accompanied overpopulation. Perhaps this had something to do with the fact that their first two children did not survive. Sometime between 1861 and 1863, the family moved out of the central district to the village of Springburn where the standard of living was much better.

Springburn's growth reflected the growth and development of the Scottish railways and locomotive production. The village took its name from a 'spring' that flowed from Balgray Hill to form the northern boundary of Glasgow. Springburn was a town the grew along with the railways. The land on which it stood was always considered within the environs of Glasgow, but as late as 1820 it consisted of a few weavers' cottages and an inn with the curious name of Lodge my Loons. All this was soon to change.

In the 1840s Springburn was transformed from a rural community to the largest locomotive building center in Europe. There might have been some risk in locating major industries so far from the population center, but those risks were reduced by the construction of new housing that would attract the most able workers from Glasgow. Further, monetary incentives were given to Glasgow's merchant class to build large single family homes in the district.

Eventually, Springburn became the home of the Hyde Park Locomotive works, the Cowlairs works, and the St. Rollox works (which was owned by the Caledonian Railway). The St. Rollox engine shed was near the workshop off Springburn Road which was convenient for William Smith who lived with his family at 121 Springburn Road. Lillias' brother, Dr. James Allan Smith, located his surgery at 526 Springburn Road. Ironically, this move out of Glagow center brought the Smiths closer to the little village of Auchinairn where Lilias Allan had married James Smith thirty years earlier. In fact, Cadder parish church was nearby, and Cadder cemetery became the location of the family burial plot.

In his later years, James Smith, who had abandoned his loom, would accompany his son, Dr. J.A. Smith, when he was called out on medical emergencies such as an accident in one of the shops or in a mine. As he grew older he became quite frail, and one day was caught by a sudden gust of wind that threw him against the iron gates of the cemetery. He sustained internal injuries, and this time his son attended him. Sensing the futility of his son's efforts, he is remembered to have said, "You can't make an old man new." James Smith did not recover from his injuries, and was buried at Cadder. An era ended with his passing, for he was a man who had begun his life when the handloom was high technology, and his life ended in the age of steam.

Steam represented the future for William Smith who had become an engine driver on the Caledonian Railway, and the high technology of the 1860s was Benjamin Conner's great 2-2-2 eight-footer, a locomotive that had the industry talking. The oustanding difference between later engines was the towering 28-spoke, 8 ft 2 inch driving wheels encased in slatted, paddle-box splashers. They were manufactured by Walter Neilson at the Hyde Park works, and in the blue livery of the Caledonian Railway, a Conner Eight-footer became the talk of London's International Exhibition of 1862.

Life on the railway was not easy. Usual practice on the Caledonian was a 15 1/2 hour work day for its drivers, and a five or six day work week. There are documented accounts of up to 23 hour shifts on some runs. To offer incentive for their crews, bonuses were offered for record speed on certain runs. On at least one occasion, William Smith used his bonus to purchase jewelry for his wife Lillias after a speedy run to London.

For all his long hours, William and Lillias managed to have six children by 1873 when their youngest, Margaret, was born. The future must have seemed bright with a father employed in a growth industry, and three sons who could expect to find a place at the Caledonian Railway. This was not to be, however, for everything changed very suddenly. For contemporary readers, what happened next seems like an unlikely event, but it was undoubtedly common in the nineteenth century. William Smith died, at age thirty-eight. The cause of his death was shock that came on during an operation for sciatica, an operation that took place in the kitchen, and without anesthetic. Chloroform was available, but like many Victorians, William Smith feared its use.

For six months, Lillias made a daily pilgrimage to the cemetery, and could not be consoled. Finally, her family prevailed on her for the sake of her six children. She wiped away her tears, and took residence in a two room tenement at 4 Wellfield Street in Springburn. The boys slept in one room, the girls in the other. To hold the family together financially, Lillias made men's dress shirts, and provided bed and breakfast lodging for railway workers held over in Glasgow.

When William died in 1875, his oldest son, William, was fourteen. In time, he began his apprenticeship at the Hyde Park works and even worked on the great railway bridge that spanned the Forth. (Work on the Forth bridge began in 1883 and was completed in 1890. To this day, the mile-long span remains a testament to the times, when the only alternative to steam was a horse-drawn tram.) James, who was twelve at the time of his father's death, became a brass molder. Among his early projects were brass stands for his mother's flat irons. The youngest son, Adam Lillie Smith, was eight when his father died. For these three, the opportunities in Scotland were limited. The patronage system was stacked against them. Proof of this is the fact that the great railway shop at Springburn formally distinguished between 'premium apprentices', who were middle-class youth in management training, 'privilege apprentices', who were either of exceptional ability or the sons of long-time employees, and 'ordinary apprentices', who comprised the majority and would be trained as machine operators with little hope of advancement. Eventually, these three would seek their fortunes in America, but it was Glasgow's industry that had shaped their skills and abilities.

The daughters' lives underwent a transformation as well. Lillias married William Craig and they spent their married life in Springburn. Eventually, after her husband's death, she lived in Coventry, England with her daughter Jean, and died in bed on her 89th birthday. Elizabeth married Archie MacArthur, and some of their children emigrated to Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Margaret, who was named after a Margaret Allan who had died in childbirth, married William Steele, who worked at the Hyde Park locomotive works in Springburn. He was hurt in a freak accident at the workshop when a locomotive fell on his foot. A hundred men rallied to lift the engine off him. The surgeons wanted to amputate his crushed limb, but he refused to let them operate, and though he was somewhat crippled after that, he brought his family to live in Pittsburgh in the early part of the twentieth century. r fortunes in America, but it was Glasgow's industry that had shaped their skills and abilities